By Dwight Cass

Net banking industry credit provision may be negative for years to come.

The headline that crossed Bloomberg screens on October 20 likely caused many borrowers’ blood to run cold: “European Banks Vow to Slash Assets by $1 Trillion.” Coming as it did in the midst of a grim bank reporting season, this bit of tactical sabre rattling sounded particularly worrying. But it was far from the most dire projection: Morgan Stanley analysts estimate that European banks will have to cut assets by $2tn and raise about of Eur230bn by the end of 2012.

While the aggregate amount of bloodletting remains a matter for debate, banks, caught between shareholders concerned about returns on equity, and regulators concerned about capital, have little choice but to shrink their balance sheets. The EU’s plan is to recapitalize banks that cannot meet its 9 percent core capital ratio. Since investors are unwilling to step in, that means the governments will most likely have to stump up the money themselves. This could turn into an exercise that challenges the US TARP bailout in scope and consequences. While the plan is not fully fleshed out, it has already caused banks—eager to avoid the government’s warm embrace—to turn off the credit spigot while they decide how to meet the capital requirement.

Blood From Stones

This is already having ramifications for corporates, and especially those looking for acquisition financing. As of mid-October, the European syndication market for leveraged loans was more or less closed as banks sought to distribute a Eur7 billion backlog of transactions. Weakness in the junk bond market didn’t help matters, although inflows into high yield funds and loan funds moved into positive territory in the latter half of October for the first time in several months.

Banks’ increased funding costs raised the cost of buyout financing so much that the economics of many deals was no longer attractive to their financial sponsors. For example, S&P subsidiary Leveraged Commentary and Data recently posted a report called, “Lightly leveraged: 45 percent is the new 30 percent for LBO equity contributions in today’s challenging lev-fin market.”

Bankers say the situation is “optically” similar to that in May and June 2007, when collateralized loan obligation indigestion caused leveraged loan inventory on banks’ balance sheets to begin to swell menacingly. Only the banks themselves, rather than their shadow-banking brethren, are now the problem.

Among the deals caught out by the market’s near-shutdown are France Telecom’s Eur2 billion sale of Orange Switzerland and the 1.5 billion pound sale of British food company Iceland.

For corporate treasurers and financial sponsors, things may not turn around soon. Lean-market technologies meant to lure bank lenders into deals, such as upward-flex pricing, mini-perm loans, seller participation in financing packages and robust pricing on institutional tranches are being used or considered. And newer options, such as those involving specialized credit funds in financing packages, are under consideration. But bankers say those will not be able to provide meaningful amounts of leverage in multi-billion-dollar buyouts.

US regional banks have to cut expenses by up to 40 percent in order to attract new investor capital and meet regulatory requirements.

These loan provisions may prove to be ineffective lures for banks. European banks, and French banks in particular, believe they will be unable to hit their capital targets, so they are dumping assets. BNP and Soc Gen, in particular, have been marketing a combined Eur150 billion of loan portfolios and other risk assets.

These are not all leveraged transactions either; the banks are selling high-quality loans, including project finance-related loans, and cutting back sharply on extending dollar-denominated loans (See: “Capital Markets: Eurozone Crisis Makes Dollar Loans a Rarity” on iTreasurer.com) demonstrating how desperate they are for capital.

In fact, in total, European banks will need to raise about Eur100bn in new capital.

American Unexceptionalism

Things are nearly as grim in the US. The big banks, as expected, posted third-quarter losses—including Goldman Sachs. Scary news emerged from several institutions that put their long-term viability (and their respect for clients) in serious question.

In particular, Bank of America moved an undisclosed amount of Merrill Lynch’s derivatives book into its FDIC-guaranteed, depositor-funded bank, apparently in an attempt to avoid having to pay higher collateral costs due to its downgrades.

If this is true—and the bank has yet to clear the issue up—it shows how dear capital has become to US money center banks, and how little they care about their relationships with clients.

Regional and mid-sized banks are also under capital pressure. Turnaround shop Alvarez & Marsal said in a report in October that US regional banks have to cut expenses by up to 40 percent in order to attract new investor capital to meet regulatory requirements. The firm says that this will force banks to merge, and it predicts that the number of US banks will fall by one-third in the next 10 years.

The firm says that only seven of the 25 largest US regional banks are trading above book value, meaning the others are ripe for acquisition. Alvarez expects only three of the 25 to have a return on equity higher than their cost of equity by 2013.

The Return Gap

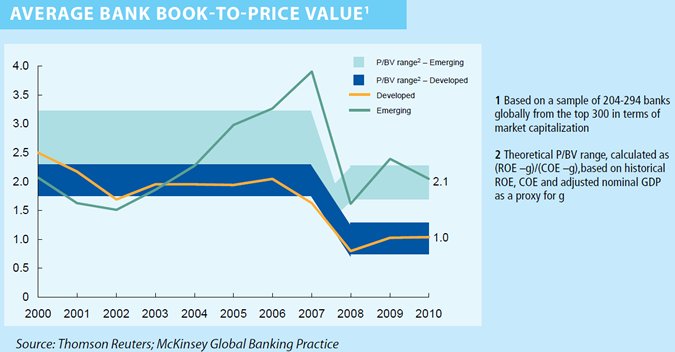

Industry-wide, the banks are in an untenable situation, and one that lending to corporates at traditional rates and fees will only worsen. A recent report by McKinsey & Co. (“The state of global banking —in search of a sustainable model”) lays out the problem:

“In 2010, the US and European banking industries delivered Returns On Equity (ROE) of 7 percent and 7.9 percent respectively. Even when these returns are ‘normalized’ by assuming loan losses equivalent to the 2000-07 average plus a ‘buffer’, the 2010 figures would only increase to 9.3 percent in the US and 9.2 percent in Europe. At this level, banks’ ROE is still some 1.5 percentage points below their cost of equity, which averaged globally 12 percent last year. Even before the industry has digested the additional capital requirements from Basel III, Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFI) surcharges and other national ‘finishes’, developed country banking is facing a significant ‘return gap’.”

McKinsey believes that, to close this gap, US banks will need to grow net profits from $121bn last year to $312 bn in 2015 if they are to achieve a 12 percent ROE. This implies annual profit growth of almost 20 percent, and profit levels almost double those likely under McKinsey’s forecasts for 2015.

And that’s assuming bank cost of equity does not rise even higher. European banks, meanwhile, will need to double profits from $166 billion in 2010 to $328 billion in 2015, according to the consulting firm.

Factors Driving Return Gap

The return gap for banks is said to be enormous; some say larger than the total profits of some whole industries combined. What’s driving the gap?

- Increasing regulation, especially Basel III and SIFI capital charges;

- Increased funding costs due to the fragmentation of Eurozone capital markets by the PIIGS crisis;

- Growth gap between emerging and developed economies;

- Shifts in consumer behavior, especially the move to digital.

Glimmers of Hope

While they’re waiting for their bankers to return their calls, treasurers can take some solace in knowing that not everyone thinks that the new capital requirements and the return versus return-on-equity gap will doom lending. The Bank for International Settlements estimates that each one percentage point increase in capital requirements will only raise the cost of a loan by 13 basis points.

There are those who believe the analysis by McKinsey—which is not unique—fails to take into account the fact that reducing the balance sheet reduces risk, which should reduce the cost of equity, eliminating the return gap. That proposition has yet to be tested. After all, few would argue that banks are any safer now than they were a few years ago, even if they believed the rosy risk scenario.

Optimists also argue that the regulatory capital requirements can be met through retained earnings. Researchers at the Pew Financial Reform Project said last year that, “A four percentage point increase in the level of common equity as a percentage of the roughly $7.5bn of loans in the US banking system would require about $300bn of new equity.

This would represent approximately a 20 percent increase in the existing $1.4 trillion of equity. Put another way, this could be obtained by retaining roughly two years’ worth of the system’s earnings, assuming even a 10 percent ROE for the banks as a whole.”

Pew acknowledges that external capital raisings will be necessary also, but the earnings approach will make them less onerously large.

While the long-term impacts of bank regulation and market developments on corporate finance cannot be known, it is best for company executives to keep a close eye on their banking relationships to maintain their access to capital.